Asignment:

Italian banks after the referendum

A state rescue of Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena, the world’s oldest bank, looks probable

THE first casualty was Matteo Renzi’s hold on office. As he had promised, Italy’s prime minister resigned on December 7th, three days after voters rejected his proposals to overhaul the constitution.

The second is likely to be a planned private-sector recapitalisation of Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena, the country’s third-biggest bank and the world’s oldest. As The Economist went to press, the scheme’s chances looked slim. A government rescue was reportedly being prepared.

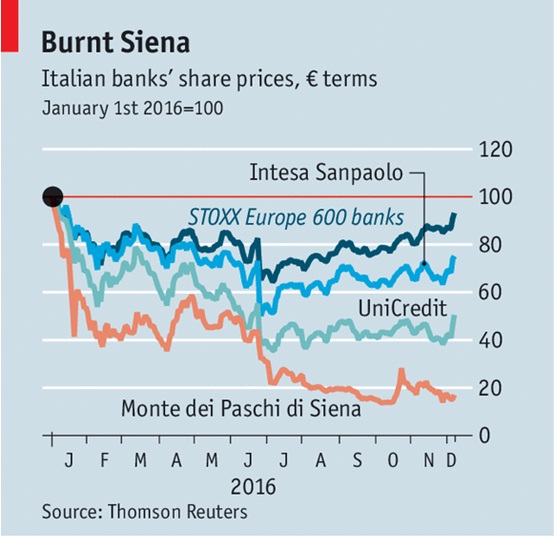

Monte dei Paschi has been in trouble for years. It has already had two state bail-outs and frittered away €8bn ($10bn) raised in share sales in 2014 and 2015. Its stockmarket value has dwindled to €600m, having fallen by 85% this year (see chart). Its non-performing loans (NPLs), even after provisions, are 21.5% of its total; the gross figure is 35.5%.

In July it fell ignominiously short in European stress tests, ranking 51st of 51 lenders. The European Central Bank, its supervisor, asked it to raise more capital by the end of the year. This week the bank asked for more time.

Pre-empting the test results, Monte dei Paschi devised a plan with two investment banks, J.P.Morgan and Mediobanca. It would dispose of €27.7bn-worth (gross) of bad loans. The beautified bank would be injected with €5bn of equity: some from a voluntary debt-for-shares swap which has already raised €1bn; the rest from a share issue, with an “anchor” investor, likely to be Qatar’s sovereign-wealth fund, providing the bulk. In October, Monte dei Paschi also unveiled a new business plan.

Alas, investors’ interest may well have been contingent on political stability. The hope is that the swift nomination of a new government could yet persuade them to part with their cash. But if, as seems likely, they demur and the state steps in, how might it do so?

Awkwardly, Italy is constrained by European Union “resolution” rules, which came fully into force this year, aimed at avoiding repeats of the bail-outs in several countries that followed the financial crisis of 2008.

If banks receive state aid, they are in effect deemed bust; bondholders as well as shareholders must accept losses. In Italy, however, small investors—who are usually depositors, too—account for a large share of junior bonds.

A “bail-in” of bondholders in four small banks late in 2015 caused uproar (at least one investor took his own life). The authorities have been desperate to ensure the same does not happen at Monte dei Paschi, where 40,000 households own €2bn-worth of its bonds.

There may be room for manoeuvre. The rules allow the “precautionary and temporary” recapitalisation of a bank to “preserve financial stability”. The bank must be solvent; the injection must be on market terms; and the capital must be needed to make up a shortfall identified in a stress test, or similar exercise—like the one Monte dei Paschi failed in July.

That may open the way for the Italian treasury—which, with 4% of Monte dei Paschi, is already the biggest shareholder—to supply equity, with a view to selling when all is calmer.

Even with a precautionary recapitalisation, bondholders have to bear some of the burden. But with some nifty legal footwork they could be compensated without falling foul of state-aid rules. Many who bought bank bonds were under the false impression that they were as safe as deposits. Even so, sorting out compensation for mis-selling could be a messy affair.

Although Monte dei Paschi is the biggest cloud over Italy’s banking system, other lenders are also seeking capital. UniCredit, the country’s biggest bank, intends to sell its asset-management arm to Amundi, a French firm, and this week agreed to sell its stake in a Polish bank. It is due to unveil a strategic review on December 13th and plans a share issue in 2017.

Much-needed consolidation is also on the way. A merger agreed in October between Banco Popolare and Banca Popolare di Milano will create a lender bigger than Monte dei Paschi.

Popolare di Vicenza and Veneto Banca, two banks held by Atlante, a private fund set up at the government’s behest, are also likely to unite. UBI Banca may acquire three of the four small banks put into resolution a year ago.

In a country where bank branches outnumber pizzerias, that should help. Sales of NPLs have picked up in 2016. But in an economy that has scarcely grown since the birth of the euro, is likely to expand by just 0.8% this year and faces political limbo, nothing can be taken for granted. Least of all at Monte dei Paschi.

For more details see the attachment.

Attachment:- Article22.zip