Case Study:

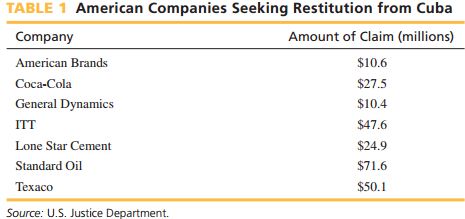

Cuba is a communist outpost in the Caribbean where “socialism or death” is the national motto. After Fidel Castro came to power in 1959, his government took control of most private companies without providing compensation to the owners. American assets owned by both individuals and companies worth approximately $1.8 billion were among those expropriated; today, those assets are worth about $6 billion (see Table 1). President Kennedy responded by imposing a trade embargo on the island nation. Five decades later, when Fidel Castro finally stepped down, no significant changes in policy were made. In 1990, Castro opened his nation’s economy to foreign investment; by the mid-1990s, foreign commitments to invest in Cuba totaled more than half a billion dollars. In 1993, Castro decreed that the U.S. dollar was legal tender although the peso would still be Cuba’s official currency. As a result, hundreds of millions of dollars were injected into Cuba’s economy; Cuban exiles living in the United States were the source of much of the money. Cubans were able to spend the dollars in special stores that stocked imported foods and other hard-to-find products. In a country where doctors are among the highest paid workers with salaries equal to about $20 per month, the cash infusions significantly improved a family’s standard of living. In 1994, mercados agropecuarios (“farmers markets”) were created as a mechanism to enable farmers to earn more money. Cuba desperately needed investment and U.S. dollars, in part to compensate for the end of subsidies following the demise of the Soviet Union. Oil companies from Europe and Canada were among the first to seek potential opportunities in Cuba. Many American executives were concerned that lucrative opportunities would be lost as Spain, Mexico, Italy, Canada, and other countries moved aggressively into Cuba. Anticipating a softening in the U.S. government’s stance, representatives from scores of U.S. companies visited Cuba regularly to meet with officials from state enterprises. Throughout the 1990s, Cuba remained officially off-limits to all but a handful of U.S. companies. Some telecommunications and financial services were allowed; AT&T, Sprint, and other companies have offered direct-dial service between the United States and Cuba since 1994. Also, a limited number of charter flights were available each day between Miami and Havana. Sale of medicines was also permitted under the embargo. At a State Department briefing for business executives, Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs Alexander Watson told his audience, “The Europeans and the Asians are knocking on the door in Latin America. The game is on and we can compete effectively, but it will be a big mistake if we leave the game to others.” Secretary Watson was asked whether his comments on free trade applied to Cuba. “No, no. That simply can’t be, not for now,” Watson replied. “Cuba is a special case. This administration will maintain the embargo until major democratic changes take place in Cuba.” Within the United States, the government’s stance toward Cuba had both supporters and opponents. Senator Jesse Helms pushed for a tougher embargo and sponsored a bill in Congress that would penalize foreign countries and companies for doing business with Cuba. The Cuban-American National Foundation actively engaged in anti-Cuba and anti-Castro lobbying. Companies that openly spoken out against the embargo included Carlson Companies, owner of the Radisson Hotel chain; grain-processing giant Archer Daniels Midland (ADM); and the Otis Elevator division of United Technologies. A spokesperson for Carlson noted, “We see Cuba as an exciting new opportunity—the forbidden fruit of the Caribbean.” A number of executives, including Ron Perelman, whose corporate holdings include Revlon and Consolidated Cigar Corporation, were optimistic that the embargo would be lifted within a few years. Meanwhile, opinion was divided on the question of whether the embargo was costing U.S. companies once-in-a-lifetime opportunities. Some observers argued that many European and Latin American investments in Cuba were short-term, high-risk propositions that would not create barriers to U.S. companies. The opponents of the embargo, however, pointed to evidence that some investments were substantial. Three thousand new hotel rooms were added by Spain’s Grupo Sol Melia and Germany’s LTI International Hotels. Both companies were taking advantage of the Cuban government’s goal to increase tourism. Moreover, Italian and Mexican companies were snapping up contracts to overhaul the country’s telecommunications infrastructure. Wayne Andreas, chairman of ADM, summed up the views of many American executives when he said, “Our embargo has been a total failure for 30 years. We ought to have all the Americans in Cuba doing all the business they can. It’s time for a change.” The Helms-Burton Era The Helms-Burton Act brought change, but not the type advocated by ADM’s Andreas. The toughened U.S. stance signaled by Helms-Burton greatly concerned key trading partners, even though Washington insisted that the act was consistent with international law. In particular, supporters noted that the “effects doctrine” of international law permits a nation to take “reasonable” measures to protect its interests when an act outside its boundaries produces a direct effect inside its boundaries. Unmoved by such rationalizations, the European Commission responded in mid-1996 by proposing legislation barring European companies from complying with Helms-Burton. Although such a “blocking statute” was permitted under Article 235 of the EU treaty, Denmark threatened to veto the action on the grounds that doing so exceeded the European Commission’s authority; its concerns were accommodated, and the legislation was adopted. Similarly, the Canadian government enacted legislature

court orders regarding sanctions. Also, Canadian companies that complied with the U.S. sanctions could be fined $1 million for doing so. In the fall of 1996, the WTO agreed to a request by the EU to convene a three-person trade panel that would determine whether Helms-Burton violated international trade rules. The official U.S. position was that Helms-Burton was a foreign policy measure designed to promote the transition to democracy in Cuba. The United States also hinted that, if necessary, it could legitimize Helms-Burton by invoking the WTO’s national security exemption. That exemption, in turn, hinged on whether the United States faced “an emergency in international relations.” Meanwhile, efforts were underway to resolve the issue on a diplomatic basis. Sir Leon Brittan, trade commissioner for the EU, visited the United States in early November with an invitation for the United States and EU to put aside misunderstandings and join forces in promoting democracy and human rights in Cuba. He noted: By opposing Helms-Burton, Europe is challenging one country’s presumed right to impose its foreign policy on others by using the threat of trade sanctions. This has nothing whatever to do with human rights. We are merely attacking a precedent which the U.S. would oppose in many other circumstances, with the full support of the EU. In January 1997, President Clinton extended the moratorium on lawsuits against foreign investors in Cuba. In the months following the Helms-Burton Act, a dozen companies ceased operating on confiscated U.S. property in Cuba. Stet, the Italian telecommunications company, agreed to pay ITT for confiscated assets, thereby exempting itself from possible sanctions. However, in some parts of the world, reaction to the president’s action was lukewarm. The EU issued a statement noting that the action “falls short of the European Commission’s hopes for a more comprehensive resolution of this difficult issue in trans-Atlantic relations.” The EU also reiterated its intention of pursuing the case at the WTO. Art Eggleton, Canada’s international trade minister responded with a less guarded tone: “It continues to be unacceptable behavior by the United States in foisting its foreign policy onto Canada, and other countries, and threatening Canadian business and anybody who wants to do business legally with Cuba.” In February, the WTO appointed the panel that would consider the dispute. However, Washington declared that it would boycott the panel proceedings on the grounds that the panel’s members weren’t competent to review U.S. foreign policy interests. Stuart Eizenstat, undersecretary for international trade at the U.S. Commerce Department, said, “The WTO was not created to decide foreign-policy and nationalsecurity issues.” One expert on international trade law cautioned that the United States was jeopardizing the future of the WTO. Professor John Jackson of the University of Michigan School of Law said, “If the U.S. takes these kinds of unilateral stonewalling tactics, then it may find itself against other countries doing the same thing in the future.” The parties averted a confrontation at the WTO when the EU suspended its complaint in April, following President Clinton’s pledge to seek congressional amendments to Helms-Burton. In particular, the president agreed to seek a waiver of the provision denying U.S. visas to employees of companies using expropriated property. A few days later, the EU and the United States announced plans to develop an agreement on property claims in Cuba with “common disciplines” designed to deter and inhibit investment in confiscated property. The U.S. stance was seen in a new perspective following Pope John Paul II’s visit to Cuba in January 1998. Many observers were heartened by Cuban authorities’ decision to release nearly 300 political prisoners in February. In the fall of 2000, President Clinton signed a law that permits Cuba to buy unlimited amounts of food and medicine from the United States. The slight liberalization of trade represented a victory for the U.S. farm lobby, although all purchases must be made in cash. In 2002, several pieces of legislation were introduced in the U.S. Congress that would effectively undercut the embargo. One bill prohibited funding that would be used to enforce sanctions on private sales of medicine and agricultural products. Another proposal would have the effect of withholding budget money earmarked for enforcing both the ban on U.S. travel to Cuba and limits on monthly dollar remittances. Also in 2002, Castro began to clamp down on the growing democracy movement; about 70 writers and activists were jailed. President George W. Bush responded by phasing out cultural travel exchanges between the United States and Cuba. In 2004, President Bush imposed new restrictions on Cuban Americans. Visits to immediate family members still living in Cuba were limited to only one every 3 years. In addition, Cuban Americans wishing to send money to relatives were limited to $1,200 per year. The early months of Barack Obama’s administration saw a rollback of various restrictions. In April 2009, for example, the president lifted restrictions on family travel and money transfers. Although reactions to the announcement were mixed, a significant increase in travel on commercial airlines will not be possible until a bilateral aviation agreement is negotiated between the two nations. At a Summit of the Americas meeting in Trinidad, President Obama declared, “The United States seeks a new beginning with Cuba. I know there is a longer journey that must be traveled in overcoming decades of mistrust, but there are critical steps we can take.” Many observers were surprised by the conciliatory tone of Raul Castro’s response to the U.S. president’s overtures. Castro indicated a willingness to engage in dialog about such seemingly intractable issues as human rights, political prisoners, and freedom of the press. “We could be wrong, we admit it. We’re human beings. We’re willing to sit down to talk, as it should be done,” Castro said. Raul’s initial response to Obama’s overture was indeed conciliatory, and in August 2009 the United States and Cuba held extended talks for the first time in at least 10 years. These talks included meetings between U.S. and Cuban governmental official and between U.S. officials and Cuban opposition figures. But the official position of the Cuban government, announced in September by Cuban foreign minister Bruno Rodriguez, was that the U.S. trade embargo should be lifted unilaterally without preconditions. Meanwhile, Obama, despite his overtures, appears to be linking any lifting of the embargo to Cuba’s making progress on human rights.

Q1. What was the key issue that prompted the EU to take the HelmsBurton dispute to the WTO?

Q2. Who benefits the most from an embargo of this type? Who suffers?

Q3. In light of the overtures U.S. President Barack Obama has made to Raul Castro, what is the likelihood that the United States and Cuba will resume diplomatic and trade relations during the Obama administration?

Your answer must be, typed, double-spaced, Times New Roman font (size 12), one-inch margins on all sides, APA format and also include references.